No Hiding the Flaws in Anonymous Class Surveys

--Originally published at Learning Education

Anonymous surveys are a common occurrence in classrooms. Yet they may not be very anonymous. Through a process known as re-identification, it is quite possible that instructors could tie your responses together with your name. What survey tools have this problem? What can instructors do to reassure students that this is not happening?

Anonymous surveys are a very important part of a course, from gauging student backgrounds at the start of the course, to getting feedback about how the course was taught near its end. For the instructor, they can provide invaluable feedback on how the course has been running. For the student, it provides an opportunity to be candid and to help improve the way the course will be taught in the future. At some institutions, they even play important roles in faculty promotions:

Student ratings are high-stakes. They come up when faculty are being considered for tenure or promotions. In fact, they’re often the only method a university uses to monitor the quality of teaching.

But a critical feature of an anonymous survey relies heavily on the assumption of actual anonymity. Take for example a scenario at NYU Abu Dhabi where an instructor asked potentially too much personal information in a survey:

The survey originally asked respondents to provide information about three friends and a significant other’s sex, major, religion, ethnicity and home country. In addition, it requested that respondents rated their identified friends and significant other’s political and religious views, rate their attractiveness on a scale of 1 to 10. Respondents were supposed to provide the same information about whom they considered the most popular person in the university and themselves. Senior Alexander Peel said he felt uncomfortable by the amount of intimate information students in the Gender and Society class would have when examining responses to the survey.

The instructor defended her actions by saying that personally identifiable information like names were removed from the survey responses and that the responses were kept confidential to her and a small research team.

Overall, the survey worried the students — so what’s to stop them from answering untruthfully. My belief is that a student will stop answering truthfully when their concerns about the privacy of their responses outweighs their benefits from the results of the survey. Unfortunately this is quite a hard decision to infer; both for the student and the instructor.

So how does one effectively draw the line? In an ideal world, an instructor would like all students to answer truthfully and a student would want assurance that they will be safe from having their responses be linked back to them. Let’s take a look at a popular survey tool to see where it nets out.

Socrative

Socrative is a popular interactive online survey tool that is especially useful for live feedback during a class. One of the ways Socrative provides anonymous surveys is by hiding names (similar to the mechanism the instructor at NYU Abu Dhabi used):

When students answer, the instructor can then view the results (with the names removed):

So there are no student names and everything looks quite OK at first glance. But one could imagine the same survey as the one asked to the NYU Abu Dhabi students being asked via Socrative. The problem here is that the actual questions may give clues to a particular student in the classroom, which is exactly what the NYU Abu Dhabi students were concerned about:

England responded … by eliminating the name items from the survey… However, some students remained worried at the possibility of deductive identification. When consulted about this, England explained that although a possibility, this is not the objective of the exercise.

So it seems that Socrative provides no more assurance to students than the NYU Abu Dhabi instructor can provide, as they are using the same privacy mechanisms (removing personally identifiable information).

So where does that leave us? Do the students even have a valid concern? The answer from privacy researchers is: resoundingly yes.

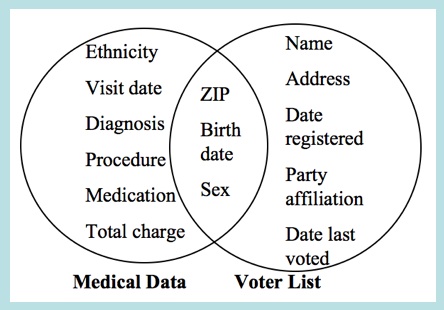

Re-Identification

Re-Identification is a technique that takes a piece of information that looks anonymous and reattach the information that goes with that anonymous data. Re-Identification has been used to identify the Netflix users and their ratings based on an anonymous data set, link names to anonymous genome project datasets, and even find the governor of Massachusetts medical records from anonymous data sets. Re-Identification is possible because there are other databases that provide missing information. So by putting together two databases one can actually learn more than either database can reveal by itself.

Re-Identification: Linking Two Data Sets Together

So how might Re-Identification work in a classroom survey? The answer revolves around linking external information with the anonymized responses. This might sound tough at first, but think about who has access to the survey results: someone who has had close contact with a person multiple times a week. Add to that the student responses are probably related to the class material; something the teacher has multiple data points from each student on (from emails, questions in class or office hours, submitted essays, homework, etc.).

Take as an example from the Socrative screenshot. What if we knew that one student in the class loved to talk about candy (but maybe they did not realize it). We now might have a strong reason to believe which student had the response “Too much candy is bad.” In this case, it may not be so bad that we have a strong suspicion who gave the response but what if the survey was based on how well the instructor did in teaching a class — a student may be quite embarrassed to find out that their candid review of the instructor was linked back to them.

What Can We Do?

In my mind, students are already implicitly aware of the issues revolving around re-identification, but may not understand its power. On the other side of the classroom, I believe that instructors are not actively trying to link student responses back to the student which made the response when they give an anonymous survey (even though they might be able to).

Yet, this does not seem to be a very fulfilling conclusion. To me, we have a gaping hole in the way anonymous surveys are presented: they can be disingenuous and not very useful to both the student (their privacy could be compromised) and the instructor (students may give fake responses for fear of compromised privacy).

Luckily there are some techniques that can still provide strong privacy guarantees. Differential privacy is a particularly strong notion of privacy that prevents users from being re-identified. There are many differentially private mechanisms that could be incorporated into classroom survey tools like Socrative. The result being a survey where students do not have to worry about their involvement in the survey being linked back to them. The increase in privacy would come at the cost of accuracy (instead of seeing “exactly 2 out of 17 people said A,” you might see something like “roughly 10-22% of people said A”).

Wrapping It Up

I hope you think twice about participating in an anonymous survey. It might just be safer to assume that the survey creator can just see your name together with the responses you made.